Road South along the Iraqi Border

(DAY 5) Almost a year to the day after I left Baghdad, today’s drive would take us within sight of the Iran-Iraq border. Traveling south along the low mountain chain that divides the two countries felt almost surreal. Here I was relaxing in a car, sipping tea with my guide while on the other side of those mountains a war raged.

Professor saw me staring at the mountains. I’d already told him about my ‘Axis of Evil tour’ and that I’d worked for the U.S. government in Iraq. Hell, I was sitting in his car wearing the desert boots Uncle Sam issued me.

Professor, and every other Iranian I mentioned it to, didn’t like the Axis of Evil thing; my tour or the original comment. “Comparing us to the North Koreans is just rude, man. We’ve got the Internet. We can talk about politics. We’re not a bunch of crazy assholes.”

He asked me about my time in Iraq. If I’d ever been shot at or anything. I told him about getting rocketed and mortared, plus the window-rattling car bomb blasts. He told me about the Iran-Iraq war when he’d guided a few Western journalists through some of these same areas for a tour of the frontlines. About artillery blasts, air attacks, and poison gas worries. About yelling at one of the TV journalists for hyping the dangers to make his report sound more exciting, “He was just standing there and lying, man. It pissed me off.”

Our conversation took place while driving past fortified fighting positions leftover from the war. Burned out Iraqi tanks and trucks were still visible along the roadside, left by the government as reminders of the martyrs’ sacrifices and the dangers that lay just over the horizon.

A welcome break in our suddenly heavy conversation came as we rolled through a long valley, empty except for a shepherd walking his flock near the road. Ever since leaving Tehran I’d occasionally glimpsed shepherds tending their flocks far in the distance. The solitary men walking their herds through the barren landscape seemed almost biblical in mood and timelessness. I was witnessing a way of life stretching back thousands of years.

Curious, I asked Professor if it’d be ok to stop and talk to the man, maybe take a picture with him. The idea seemed to intrigue Professor as well and he quickly agreed, slowly bringing the car to a stop on the road opposite the shepherd.

The shepherd stopped and stared as we pulled up. Professor quickly rolled down his window, stuck out his head, and said something to the man I couldn’t understand. The man paused and thought for a moment, then shouted an answer.

“He says no problem.” Professor had brought his head back into the car. “Hand me your camera and I’ll take the picture … and be careful of cars crossing the road (no vehicles were visible for miles). Oh, and he says try not to scare his sheep.”

I tossed my camera to Professor and hustled across the road. We’d been practicing Farsi in the car for three days now and I took advantage by greeting the man in his own language. He responded just like Professor said people would, returning the greeting with his right hand briefly touching his heart in a sign of respect and friendship.

We exchanged a couple more pleasantries while Professor lined up the shot. I turned back to Professor and reminded him to make sure no cars were coming before snapping the picture, which got me a sardonic smile.

The picture is one of my favorite from the trip. A brown, barren landscape littered with rocks and roadside trash lies behind the shepherd. The shepherd stands proudly distant to my left, walking stick in hand and flock slowly grazing in the background. Take away the trash and the man’s modern jacket and it could just as easily have been 2006 BC, as 2006 AD.

The shepherd answered some questions about his life through Professor, then seemed anxious to get back to his animals. I’d forgotten how to say goodbye but managed a thank you, wave and smile, before giving him most of the extra food I’d bought the night before. With that I got in the car and returned to our century. The shepherd went back to his flock.

Lunch

As we drove further south and slowly out of the mountains the temperature turned from January to spring. When we pulled into a dusty roadside diner for a late lunch it was even warm enough to sit outside. I was still new enough to Iranian food that all the bread and kebabs tasted pretty similar, whether at a fancy tourist place in Tehran or out here in the middle of nowhere. We sat breaking bread and watching what rolled by.

Just as Professor was telling me more about the war with Iraq and all the causalities this area had sustained we saw a guy slowly wheelchairing his way towards us alongside the dusty, garbage-strewn road. He heaved his way through the potholes and cracks in a well-practiced, patient manner. Once close he called out a greeting to one of the guys working at the restaurant, who came out and helped him over a small curb and up to one of the tables beside us.

“They are friends,” Professor said, listening in. “It seems like the guy comes here a lot for lunch.” A few other people, workers at our restaurant and other nearby shops, soon straggled over and joined the man. A comfortable camaraderie descended on the group as they ate and swapped stories. It could have been any group of 30-year-olds in any small town in the world.

Later, as we paid the bill and got ready to leave, Professor asked the waiter about the man. Our guesses had been correct; he was a local who’d lost the use of his legs from a war injury, and everyone in the group were old friends. Judging from the natural give-and-take, plus the lack of surprise or interest on the faces of passersby, no one regarded the scene as anything other than normal.

I looked up the road at where the man had come from. To be in a wheelchair, out here in a place like this, rolling through heat, dirt and garbage everyday to get lunch … wow. But, here he was, just another guy happily sitting and BSing with friends over a meal. I think about that guy sometimes when I’m having a lousy day.

We got back in the car and continued south. This whole day we’d seen a lot of military, both bases and at checkpoints along the road. At most checkpoints they would scan our car as we approached then wave us through with hardly a second look. The only time we actually had to stop the soldier just glanced in the car, exchanged greetings with Professor, then motioned us on. Judging from the number of trucks they’d ordered off the road and into inspection it was apparent they were targeting smugglers – weapons coming in and drugs going anywhere.

Professor was a good driver, far safer and more patient than I, but even he was extra careful along this road. The police would occasionally time how quickly vehicles motored from one checkpoint to the next and if too little time had elapsed you were rewarded with a scolding and a ticket. I’ve found few police forces in the world as uptight about speeding as American cops, but the Iranians are definitely close.

Lacking radar detectors Iranian drivers have come up with a more communal, cooperative system of detecting cops. As we would approach a speed trap or hidden checkpoint oncoming drivers would flash their lights and then make an odd twirling motion with their fingers as the cars neared. Judging by how anxiously or quickly they spun their fingers you got an idea of how close the fuzz was, an action I observed in every section of the country I visited. This ‘us against the police’ mindset offers a more revealing insight into how people feel about the authorities than a stack of newspapers or months of research.

History’s Footsteps

This was the day that really brought home the history of this part of the world. In one five-hour period alone I walked across the same pavement stones as Alexander, visited the Tomb of Daniel (of the lion’s den), saw remains from the civilization that invented writing, which were just down the road from the ruins of the civilization that invented the wheel. And then the view from my hotel room that night was of the world’s oldest university.

After driving for most of the day we finally arrived at our first stop. Little remains of the historic city of Susa, dating back 4000 years, other than foundations and paving stones. It’s left to the mind to recreate the huge, multi-pillared administration building that once overlooked and dominated the surrounding area. Walking through the remnants literally puts you in the footsteps of Alexander, treading the exact same paving stones through the exact same buildings.

The next stop, so close to the remains of Susa we walked to it, was the Tomb of Daniel. Professor was worried about this place, as he got anytime we neared a religious site. Pulling me aside for a moment he warned that if anyone inside asked, I shouldn’t say I was American. He thought about it a moment and then suggested Italian, “Nobody knows anything about Italians around here, so that’d be better than French or German.”

When I told him I didn’t speak any Italian, he said not to worry, “Nobody there will either.

Islam also views Daniel as holy, so the tomb, to my surprise, was packed with Muslim pilgrims. Our entrance was crowded with men – women used a separate opening somewhere further away. Squatting to remove my boots before entering was the first time on the trip I actually got nervous. The GI-issue desert boots (so comfortable and perfect for hiking in the desert I couldn’t bear to leave them at home) would have been much less of a problem had we not been so close to the Iraqi border and so many of the pilgrims not been speaking Arabic. Obviously a lot of the men here were not Persian, presumably many were Iraqi, and they might associate my boots with something they wanted dead. I’d never been so self-conscious of my size-14s.

I quickly tucked the giant things into a corner then hop-scotched my way across the other shoes to the entrance. I instantly felt out of place. The cold, slippery floor felt weird and uncomfortable through my socks. People stared. The looks were no longer friendly or curious. I didn’t belong here.

As we rounded the corner to the interior I heard wailing and crying. Men stood praying and chanting. Others kissed the ornate golden tomb. Everyone looked at me. I swallowed and lined up a picture, after first checking with Professor.

“It’s ok, but hurry.”

I snapped the picture. Then Professor, to my surprise, told me to stand in front of the tomb while he got a shot of me. I tried to stand in front of the tomb but men kept coming and going, forcing me to move and delaying the shot. Looking at them made me thankful I at least had a beard – all the other men, except Professor, had one.

“Where are you from?”

Here we go. A young man, bearded of course, had approached. I could literally see the religious fervor in his eyes.

“Italy. You?”

“I’m from here. Do you believe in Mohamed?”

People were stopping to observe. Professor looked worried. My irritation with pushy religious people commandeered my tongue. “Never thought about it. You?”

“Of course! You can see we Muslims believe in your prophet [here meaning Daniel]. Why don’t Christians believe in ours?” A murmur went through the quickly gathering crowd. I don’t know how much English they understood but it didn’t take a genius to hear the words Mohamed, Muslim, and Christian to figure out what was going on. “It doesn’t seem fair that Muslims believe in your prophets but you don’t believe in ours.”

“I guess life isn’t always fair.” I answered, suddenly feeling angry.

At this Professor grabbed my arm, smiled at the young man, and said we’d better be going. The young man smiled back. The crowd stepped aside to let us pass.

All was silent for a couple of seconds as we made our way back down the hall toward the front. Then a sudden burst of conversation told me the others must have been asking the young man what had been said. Professor listened for a second then told me to hurry and get my boots. Fortunately, they weren’t hard to find.

“I think it’d be better to move on to the next place on the tour. There are some nice paintings on another part of the Tomb but …”

“No problem. Let me lace these things up and we can get back to the car.”

As we walked out of the Tomb area a couple of men suddenly approached and started talking to Professor in Arabic. I scowled and tried to loom over the conversation, thinking we weren’t going to make it back to the car without getting into a fight. Professor saw my expression and read my mind.

“Don’t worry. They’re pilgrims. They’re just asking for directions.”

The two men smiled kindly, thanked us for our time, and walked on toward the Tomb. I told myself to calm down. One religious nut didn’t mean everyone was out to get me. We made our way back to the car.

As we approached Professor got a quizzical look on his face.

“What’s wrong?”

“Some asshole stole my hubcap!” Sure enough, one of the Peugeot’s hubcaps was missing.

“I guess this isn’t our town.”

“Yeah, let’s get the hell out of here.” And with that we took off.

I wonder to this day if his car was targeted because of my presence (before entering our first stop, the Susa remains, Professor had been required to fill out a form, common at tourist sites, stating my name and nationality). The car next to ours had been fine. The guard station where we’d had to fill out the form was in plain sight, only 10 yards from the car.

Chogha Zanbil

We approached this site through a giant sugar plantation, where I first heard the story of the mullah and the sugar cube. Perhaps apocryphal, I heard the story so many times I came to believe it through sheer repetition.

It seems a while back a foreign company opened a sugar factory in Iran and started producing sugar in cubes. The ubiquitous things one now sees at every restaurant, tea shop, rest stop, and tea time throughout the country. Unfortunately for the new company, a certain well-known mullah took a dislike to the newfangled cubes and forbade Iranians from using them. To the mullah the cubes were somehow un-Islamic. God had apparently intended for Iranians to only use powdered sugar.

The company, its sales plummeting, went to the mullah to see about getting his ruling changed. After the meeting, the company head wisely decided to make a donation, the size of which varied according to the level of disgust the storyteller had with the current mullah-led government. Soon after the donation the wily mullah announced it would be ok for good, god-fearing Iranians to use the sugar cubes, as long as they first dipped them into pure Iranian tea. After hearing the story I started paying attention and not once in any café in the country did I see someone pop a cube in their mouth without first dipping it into their tea.

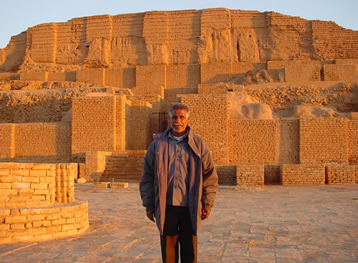

We approached Chogha as the sun was beginning to set. The cloudless skies and dying flames of the sun made the 3000-year-old orange bricks glow with life. This is the largest pyramid outside Egypt, only it had been forgotten, literally buried under time and sand, for over 2500 years until its accidental rediscovery in the mid-1930s. Carefully unearthed in fits and starts over the decades since, the upper parts of the pyramid, here called a ziggurat, had collapsed, but the remaining stories attest to the size and power once held by Chogha’s rulers.

As we walked into the interior at the ziggurat’s base we were approached by an old man who offered to show us around. He lived in the area, spoke more Arabic than Farsi, and gave private tours as a way to supplement his income. Once we started it seemed that few things; not roped-off areas, not closed gates, not even ‘keep out’ signs, could keep this older gentlemen from giving me the tour of my life. Even Professor, who’d visited the site dozens of times, was impressed.

Within minutes, I found myself walking deep inside the compound, climbing stairs reserved three millennia ago for kings and priests. Bringing home the humanity of the ancient denizens, our guide pointed out animal tracks and a small footprint preserved in the 3000-year-old bricks.

Exiting the interior of the compound I gave our elder guide the most well-earned tip ever. An action noticed by some passing Iranian tourists, who thought it was a bribe, and teasingly scolded him, “Ah, ah, ah, we saw that!”

During our tour of Chogha we’d come across several groups of Iranian tourists, all of them very curious about the foreigner. Most would give Professor and I a questioning look, to which I’d respond with my newfound Farsi. Then stare at them dumbly when they said something I hadn’t learned yet. Professor would finally come and bail me out, translating the, “Where are you from? What do you do? What do you think of Iran?” questions everyone asked. Next would come pictures, always men only unless the women were specifically invited to join us.

As we were walking back to the car one of the kids I’d said hello to earlier, this one because I’d liked the contrast of his Levi’s t-shirt and the age-old ziggurat, came running up to us, spoke with Professor, then handed him something. Professor smiled back and gave the kid a friendly pat on the head. With that the boy, embarrassed, quickly ran back to his father and uncle.

Professor turned to me with a smile and said something about Iranian children being very shy and innocent toward foreigners. So shy, in this little boy’s case, that he’d asked Professor to give me the gift he’d brought and tell me how much he hoped I enjoyed my visit. It was a small set of prayer beads, about the size of a necklace, that Muslims use as they sit and think or pray. The beads are sitting on my lap as I type this – fingering through them is the best method for overcoming writer’s block I’ve ever found.

We got back into the car as the sun set, still with an hour left in our drive to the southern oil city of Ahvaz, so we drank some of the local tea to help keep us awake. As I dipped my sugar cube into the tea, more to loosen it a bit than out of any sort of religious conviction, I smiled at the story of the mullah and the nearby sugar cube factory.

Ahvaz

The night road to Ahvaz was partially lit by fires burning the excess gas off the top of the area’s countless natural gas wells. Seizing these same wells had been one of the main goals of Hussein’s invasion. They certainly made for an eerie landscape as we got closer to town.

The city showed few remaining signs of the war – our hotel turned out to be one of the most scenic of the trip, overlooking a park-lined river that ran through downtown. Hungry, we quickly dumped our bags and left to find some food. Since it was Friday, the Muslim holy day, not much was open. We ended up on an extended walk to a brightly-lit restaurant we’d seen on the other side of the river. Once over a narrow bridge we had to pass through a poorly-lit park to get there.

With memories of living in Washington, DC still fresh in my mind, it felt a little dangerous to walk through a dark park late at night, especially given how much I stuck out. I needn’t have worried though, the groups of men in their teens and 20s were interested in one thing only, cars.

It felt like walking onto the set of a Persian remake of a Hollywood car movie. All around us were the sounds of growling after-market exhausts, cranking stereos, and souped-up engines, plus enough running lights to blot out the sun. A few people saw the foreigner and gave me a wave or “hello” but most were far more interested in looking cool and impressing any women that might have been daring enough to come around. The scene felt like American Graffiti meets Fast and Furious. I was coming to a stop and staring so much that Professor had to urge me to get a move on before the restaurant closed.

Upon entering the restaurant we got the brief stares and momentary conversation pause I was used to from other travels in Asia. Soon though, as always, everyone went back to their families and meals as Professor and I proceeded to order half the menu. It’d been a long day, with miles of walking through the numerous sites, plus the long hike across the river and through car show park to get here, and we were starving.

As we waited for the food, the restaurant’s display of flags caught my eye. In Iran, it seemed that every hotel and decent-sized restaurant didn’t feel its décor was complete without a few short rows of the world’s flags on tiny pedestals. Out of curiosity I’d made it a habit to look for an American flag, which I’d yet to see. All the other major country flags were there, even for countries like England that the Iranians didn’t like much more than the States, but there was never an American flag. Interestingly, I was able to see the North Korean, and even the Iraqi flag several times, including here at this restaurant. But I’d still yet to see an American flag …

After the meal we headed back through the park, but by now it was pretty late and not nearly as crowded as before. A few cars banzai’d their way past but no one stopped to talk. Once back across the bridge we split up, Professor back to the hotel, me off on another quest for the Internet.

Tonight’s ‘Coffee Net’ turned out to be the kind of place I was looking for – a few computers, some couple chairs, and a bunch of young people sitting and chatting or playing online games. The guy running the place was surprised, but covered it up well and pointed me to an empty workstation. I sat down, and to my surprise saw all the computers were running the pre-release, beta version of Microsoft Vista. How in the hell did they get that? The latest update for Windows, nearly a year before its release to the public and still in testing, up and running in an Internet café in middle-of-nowhere Iran. The power of the Internet, and the closeness of the tightly-knit international geek/hacker community, once again took me by surprise.

After spending a frustrating hour dealing with the café’s slow Internet connection, it was time to go. As I paid the bill I complimented the guy on his Vista systems, which got me an amused smirk. Then I was out the door and on my way back to the hotel.

Only a few paces from the café I looked up to see a couple of policemen walking right toward me. My blood froze. It’s late at night. I’m alone, and I’m pretty sure it’s not kosher for an American to be wandering the streets of Iran by himself. I quickly ducked my head, and earnestly willed my beard to look bigger and darker. I tensed as they passed, but no problem. As their footsteps faded I hurried back to the hotel.

Safely back in my room, I picked up one of the better books on modern-day Iran I’d found, Searching for Hassan. I read the part on Shiraz – Iran’s major southern city and the place we were heading at daybreak.